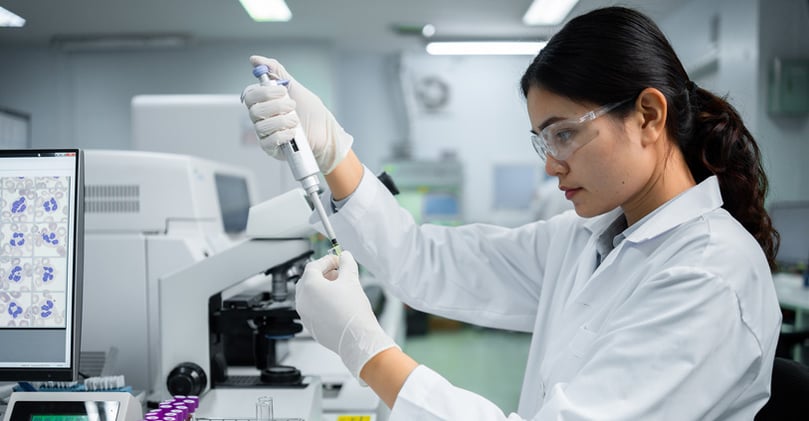

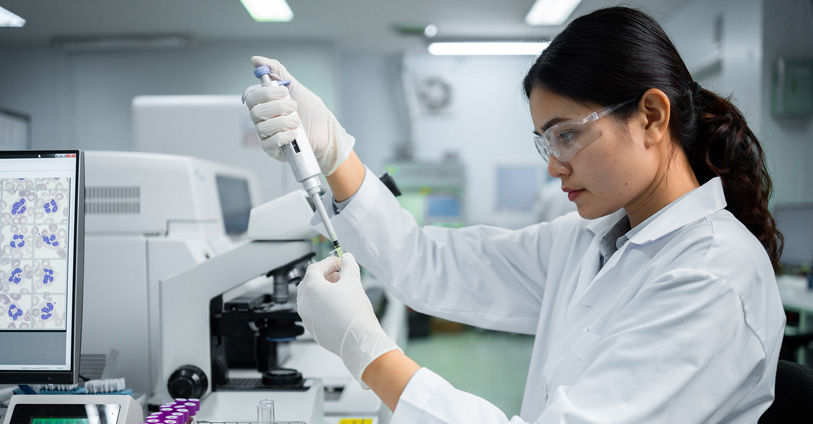

Flow cytometry is a semi-quantitative method that is widely used for preclinical and clinical studies. Preclinical flow cytometry experiments rely on users who understand the fundamentals of setting up appropriate standards and controls, but these protocols do not need to typically meet specific clinical standards. In contrast, clinical flow cytometry protocols require adherence to good clinical laboratory practice (GCLP) standards. Here we provide an overview of GCLP standards with respect to clinical flow cytometry.

GCLP guidelines were developed in the early 2000s to provide a regulatory framework for labs performing assays for HIV-1 clinical trials. A large portion of these assays were flow cytometry-based[1] and were being conducted on flow cytometers at multiple global sites, thus necessitating standardization. GCLP guidelines are a type of regulatory standard, with similarities to good laboratory practice (GLP) and clinical laboratory improvement amendments (CLIA) and have become essential to harmonizing clinical laboratory work taking place at different sites and times for clinical trials. GCLP standards can be applied to labs carrying out safety, diagnostic, or endpoint assays, and have been critical to the evaluation of immuno-oncology drugs and biologics being evaluated in clinical trials.

GCLP guidelines include personnel organization and training, equipment maintenance and validation, the development and validation of standard operating procedures (SOPs), assay development and validation, and audits to identify discrepancies in any of these areas[2]. GCLP procedures for clinical flow cytometry assure that flow cytometers at different sites are performing consistently and within standards. Flow cytometry reagents are parallel tested with previous lot to assure their eligibility for use in an assay. Throughout the implementation of GCLP guidelines, a laboratory must maintain a document control plan that includes all SOPs currently in use and an archive system for SOPs that are no longer in use.

A quality control (QC) program is essential to a GCLP framework as it allows for the monitoring, documentation, and recognition of QC problems. QC programs track test standards, positive and negative controls, reagent performance, QC data analysis and logs, and parallel testing. QC is especially important for clinical flow cytometry to assure that the appropriate cell populations are being analyzed in a consistent and reproducible manner.

A proficiency testing program is another critical component of GCLP program because it involves analysis of a common set of samples by multiple laboratory sites to assure that performance can meet specific criteria[3]. Clinical flow cytometry assays typically lack “gold standard” samples for evaluation because cells that are being analyzed in this manner are subject to intra- and inter-sample variability. Nonetheless, samples can be expected to fall within a specific predetermined range, thus assuring that the GCLP-compliant protocol, users, and equipment are performing proficiently.

A proficiency testing program is another critical component of GCLP program because it involves analysis of a common set of samples by multiple laboratory sites to assure that performance can meet specific criteria[3]. Clinical flow cytometry assays typically lack “gold standard” samples for evaluation because cells that are being analyzed in this manner are subject to intra- and inter-sample variability. Nonetheless, samples can be expected to fall within a specific predetermined range, thus assuring that the GCLP-compliant protocol, users, and equipment are performing proficiently.

GCLP standards for clinical flow cytometry are now being applied in different ways, including complex immunophenotyping of multiple immune cell subsets, comprehensive measurement of immune checkpoint molecule expression on T cells, and receptor occupancy assessment of therapeutic antibodies. The development of GCLP guidelines is often carried out with GCLP professionals who can advise on all aspects of this complex undertaking. Alternatively, individual assays, such as clinical flow cytometry experiments can be carried out by contract research organizations who are already GCLP compliant and experienced with running these assays.

[1] Todd CA, Sanchez AM, Garcia A, Denny TN, Sarzotti-Kelsoe M. Implementation of Good Clinical Laboratory Practice (GCLP) guidelines within the External Quality Assurance Program Oversight Laboratory (EQAPOL). J. Immunol. Methods. 2014;409:91-98.

[2] Sarzotti-Kelsoe M, Cox J, Cleland N, et al. Evaluation and recommendations on good clinical laboratory practice guidelines for phase I-III clinical trials. PLoS Med. 2009;6(5):e1000067.

[3] O'Hara, Denise M., et al. Recommendations for the validation of flow cytometric testing during drug development: II assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 363.2 (2011): 120-134.

Total receptor assay: The evaluation of a potential therapeutic target usually begins with an assessment of how many receptors are expressed by a given cell subset. If a receptor is abundantly expressed, it may be a difficult target to use due to potential off-target effects or the requirement of high doses of a therapeutic antibody. Measurement of total receptor involves using a fluorescently labeled antibody that binds to a receptor at a site that is different from the binding site of the therapeutic antibody of interest.

Total receptor assay: The evaluation of a potential therapeutic target usually begins with an assessment of how many receptors are expressed by a given cell subset. If a receptor is abundantly expressed, it may be a difficult target to use due to potential off-target effects or the requirement of high doses of a therapeutic antibody. Measurement of total receptor involves using a fluorescently labeled antibody that binds to a receptor at a site that is different from the binding site of the therapeutic antibody of interest.

A proficiency testing program is another critical component of GCLP program because it involves analysis of a common set of samples by multiple laboratory sites to assure that performance can meet specific criteria

A proficiency testing program is another critical component of GCLP program because it involves analysis of a common set of samples by multiple laboratory sites to assure that performance can meet specific criteria